U.S. President Donald Trump promised voters that if elected a second time, his administration would pursue mass deportations of those unauthorized to be in the country, and they appear to be looking far afield in pursuing that goal.

But the U.S. is now running roughshod over principles it has agreed to as a signatory to international refugee treaties and in its own legislation, say many organizations who advocate for refugees.

The principle of non-refoulement, in particular, is an obligation to not return migrants to countries of origin or third-party countries when their life or freedom would be threatened for reasons of race, religion or nationality, per the United Nations, or where they may subjected to human rights violations.

Those principles have been questioned in the courts as the U.S. has dealt with large flows of migrants at its borders. The previous administration only narrowly won a Supreme Court case allowing it to discontinue a program from Trump’s first term, in which asylum seekers from other countries were sent to Mexico to await their U.S. refugee claims.

The Trump administration has revived that plan, called Migrant Protection Protocols, but refugee advocates say there was a lack of protection for many migrants waiting in Mexico the first time around, as several were allegedly subjected to kidnapping and attacks, including the alleged sexual assault of a young boy from El Salvador.

The U.S. in certain cases does not have expatriation agreements with the countries of origin for some of the migrants, but it is increasingly expelling people to third countries — without notice.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said recently the goal was to expel “some of the most despicable human beings,” but it’s clear from reporting that many of the deportees don’t fit that characterization.

Here’s a look at some of the countries co-operating with the U.S., or reportedly in discussions with Washington.

Confirmed

It has been estimated that 200 migrants, including 80 children, have been deported so far to Costa Rica. The migrants sent to a rural camp in the Central American country hail from Afghanistan, Russia, China, Pakistan, India and elsewhere.

Costa Rica has announced most of the deportees would be given three-month permits for humanitarian reasons, during which they can seek asylum there or arrange ways to leave for another country.

The terms of what the country agreed to with the White House have not been transparent, the country’s English-language newspaper, the Tico Times, has reported.

President Rodrigo Chavez was forthright about the rationale for co-operating: “We are helping the economically powerful brother to the north, who if they impose a tax in our free-trade zone, it’ll screw us.”

The humanitarian organization Refugees International said the arrangements “appear to be a quid pro quo deal” to “facilitate human rights violations to avoid punitive U.S. economic measures.”

At least on the surface, the Costa Rican government appears to be willing to protect the migrants.

“If the person has a well-founded fear of returning to their country, we will never send them back,” Omer Badilla, head of Costa Rica’s migration authority, told the New York Time last month. “We will protect them.”

The Trump administration sent about 300 migrants to Panama in February, with some saying they had no forewarning as to where they were going. Initially, they were unable to leave a Panama City hotel, and then were transported to a makeshift facility in the Darien Gap.

As with Costa Rica, government officials have said they are eligible to apply for temporary humanitarian permits to remain in Panama, although the U.S. embassy in Panama in a statement on May 6 heralded the fact that 81 from the group — from countries including Cameroon, Nepal and Bangladesh — were being put on a plane yet again, apparently bound for their countries of origin.

Panama is an interesting case, in that an agreement was first struck with the U.S. in 2024, during Joe Biden’s term, and described as that administration’s “first attempt to fund deportations to a foreign country.”

The Central American country confronted waves of migrants transiting a dangerous Darien Gap route, and Washington was looking to reduce those numbers. At the time, the pilot program was said to have cost $6 million US, but the U.S. embassy said in its aforementioned May statement that it was providing approximately $14 million to Panama.

Much of the attention to date on U.S. deportations of third-party nationals has focused on El Salvador. Trump and that country’s president, Nayib Bukele, gloated about their arrangement at a recent White House meeting.

The Trump administration has offered shifting explanations as to why a group of more than 230 Venezuelan migrants weren’t merely deported to an unfamiliar country, but shipped off without criminal trials to one of the world’s most notorious prisons in El Salvador.

One Democratic lawmaker alleged the Trump administration is paying El Salvador as much as $15 million, and judges in more than one instance have questioned the vague claims and thin evidence that some of the migrants are gang members.

The Trump administration deported more than 200 immigrants by invoking the Alien Enemies Act — a wartime measure — alleging they were members of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang. Andrew Chang explains how Trump is interpreting the language of the 1798 law in order to avoid the standard immigration court system, and why experts say it’s a slippery slope.

As mentioned, Mexico is again receiving migrants from other countries expelled by the U.S. It has been reported that more than 5,400 people so far have been taken in. President Claudia Sheinbaum recently said that “most of them voluntarily decided to return to their countries,” but the status of others is not clear.

The president of Guatemala told NBC News it was willing to take third-country nationals from the U.S., but did not expect “big numbers of people” in that category. It’s not clear if any have been taken in since his February comments.

Other reported destinations

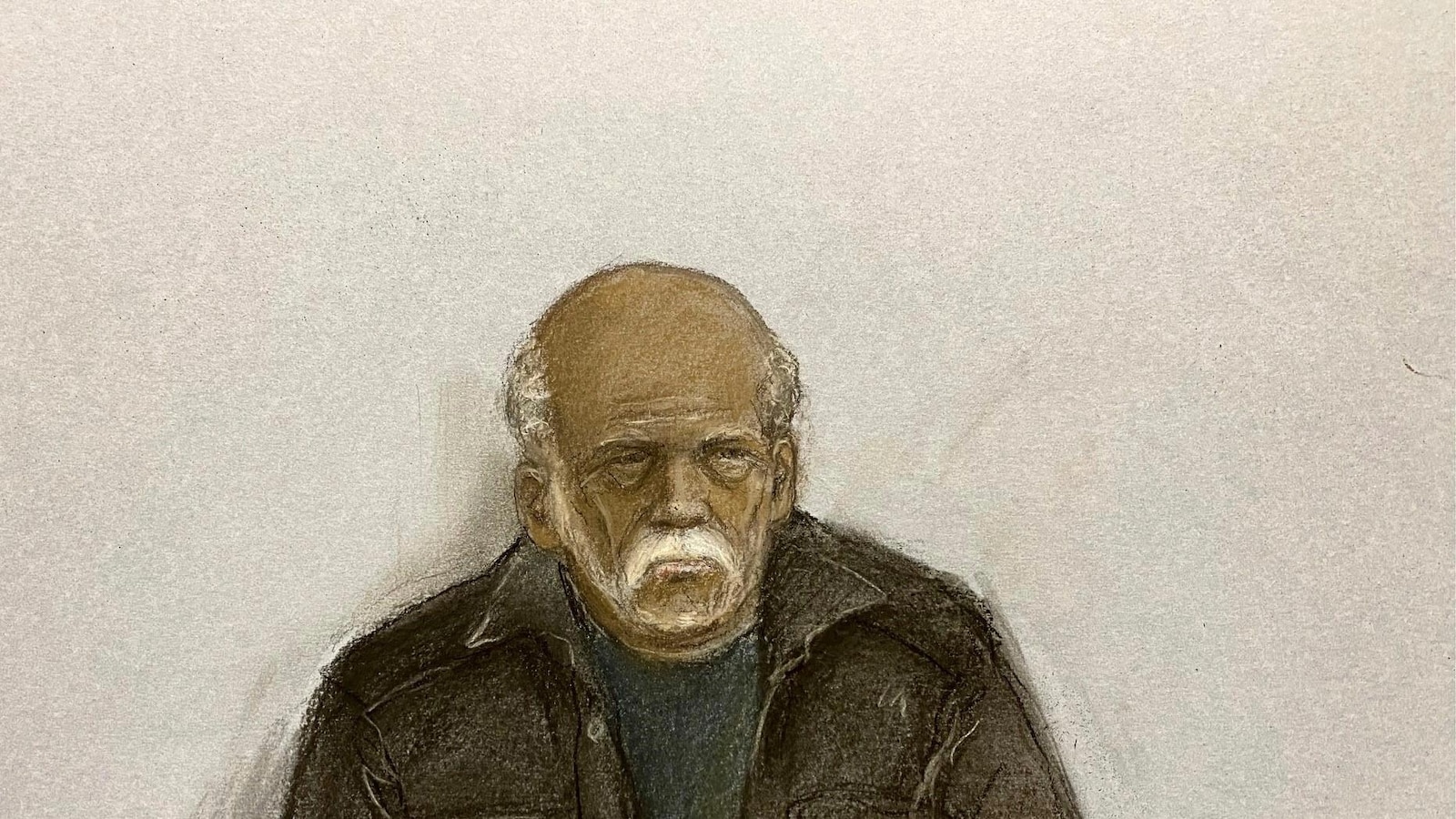

Reports emerged earlier this month of the very real possibility of the U.S. sending some deportees to Libya, with a federal judge intervening with a temporary block on those plans. The country has become a flashpoint over the past several years for its treatment of migrants from other African countries who were en route to, or returned from, European shores.

The prospect of Washington co-operating with Libya on a migrant arrangement was “dystopian,” said Human Rights Watch in a statement.

“Libya’s ill-treatment of migrants is notorious, its detention centres are hellholes, and refugees have nowhere to turn for protection,” said Hanan Salah, associate Middle East and North Africa director for the organization.

Olivier Nduhungirehe, foreign minister of Rwanda, confirmed to The Associated Press in early May that talks were underway with the U.S. about a potential agreement to host deported migrants, after telling state media the talks were in the “early stage.”

Rwanda’s longtime autocrat Paul Kagame faces no real opposition to his re-elections, as numerous human rights organizations have accused his regime of illegally detaining or disappearing dissidents and political foes.

The U.S. wouldn’t be the first country to consider Rwanda as a destination for migrants. Britain’s Conservative government was prepared to do so, even reworking legislation after the U.K. Supreme Court said in a ruling that Rwanda could not be considered a safe third country. No migrants were ultimately sent there, as the Labour Party scrapped the scheme after winning the 2024 election.

Are other governments seeking to be compensated by the U.S. in exchange for receiving migrants? It’s not clear, but the vice-president of Equatorial Guinea recently said on X that such discussions with the U.S. had taken place, an assertion that wasn’t independently confirmed. The country perennially ranks high on the list of Transparency International’s list of the most corrupt countries, and is led by the world’s longest-serving autocrat.

The Washington Post, citing U.S. government documents it had reviewed, reported on May 6 that the White House had urged Ukraine to accept an unspecified number of deportees from other countries. It wasn’t clear what the Ukrainian government’s response was, and the Department of Homeland Security didn’t respond to the Post for comment.

Trump has lamented that hundreds of billions of dollars were spent in military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine under the Biden administration after Russia’s invasion in early 2022. The White House under Trump has sought favours in return, with the two countries recently agreeing on a joint investment fund to tap into Ukraine’s mineral resources.

where-in-the-world-is-the-u-s-trying-to-deport-3rd-country-migrants

Leave a Reply