It was established by Syria’s fledgling government to restore calm in a country fractured by roughly 14 years of civil war. Instead, the Committee for Civil Peace has become a source of national strife.

Discontent is simmering among some Syrians who supported the uprising against the country’s ousted dictator, Bashar al-Assad. They now accuse the rebel leaders who toppled him of empowering a committee set up to ease internal divisions at the expense of holding remnants of the old regime to account.

Public outrage exploded during the Muslim feast of Eid al-Adha in early June when the committee released dozens of former regime soldiers, saying they were not implicated in any crimes. Now critics are calling for protests.

“What everyone has been waiting for since Assad’s fall is to see the punishment of those who committed war crimes, to see transitional justice take place,” said Rami Abdelhaq, an activist who supported the anti-Assad revolt. “Instead, we are shocked to discover there’s a release of many people.”

The peace committee was formed in the wake of the large-scale killings of minority Alawites, the sect to which Mr. al-Assad belongs. While in power, the president had made Alawites the backbone of his military forces, which fought to crush the rebellion underpinned by the Sunni Muslim majority.

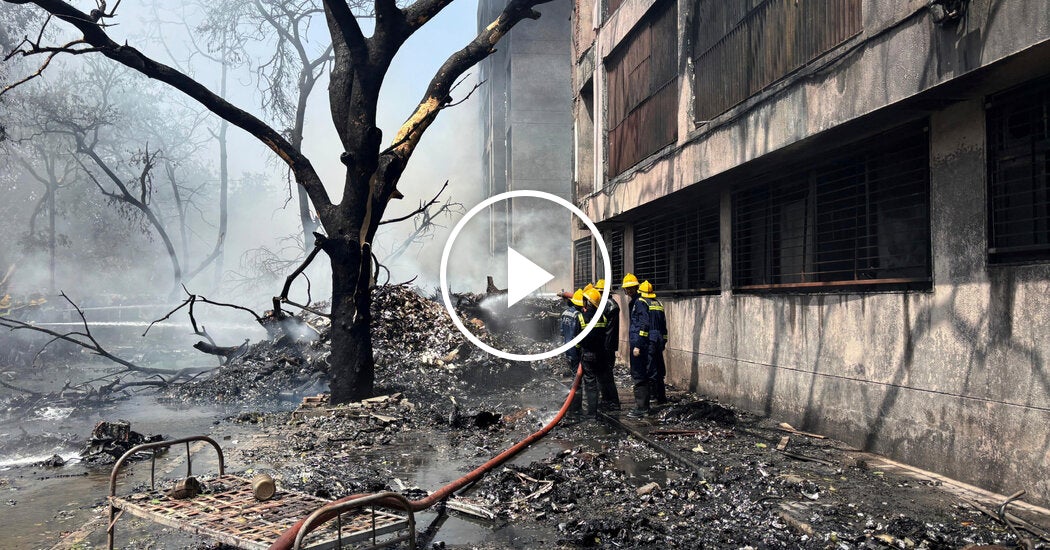

After a foiled counterinsurgency in March by former regime soldiers in a region along the Mediterranean coast, armed government supporters killed hundreds of Alawite civilians, according to human rights groups.

The committee says it is working to de-escalate tensions with Syria’s minorities. But debates over its purpose cut to the heart of a central question in post-Assad Syria: how to achieve justice and reconciliation in a population that endured decades of violent repression.

More than 600,000 people on all sides were killed in the war, according to rights groups, while tens of thousands were tortured and imprisoned. Thousands who disappeared into Mr. al-Assad’s detention centers are missing to this day.

The Assad regime’s victims are clamoring for a transitional justice process to hold those behind the crimes to account.

For some who lived under Mr. al-Assad’s rule, in particular the Alawites, the March killings on the coast cemented fears of bloody vigilante justice.

The peace committee says it aims to foster the social cohesion needed for transitional justice to function — and it has shown willingness to work with former regime figures to encourage local buy-in.

For months, there has been growing criticism over the committee’s cooperation with Fadi Saqr, an Alawite who once led the National Defense Forces, a pro-Assad paramilitary force, in Damascus, the capital.

On Tuesday, the committee held a news conference to explain its work and to try to calm tensions. Instead, the group unleashed a maelstrom.

Supporters of the anti-Assad revolt accused the committee of allowing war criminals to flee justice and demanded that Mr. Saqr help locate graves of those missing.

Critics are particularly incensed by Mr. Saqr’s involvement because they say he bears responsibility for the National Defense Force’s massacre of civilians in the Tadamon neighborhood of Damascus in 2013, and the brutal siege of rebel-held suburbs of the city during the war.

Mr. Saqr denies responsibility, saying he was appointed to lead the militia after the Tadamon massacre, and told The New York Times in a statement that he had been given no amnesty by the government.

“The state was clear with me from the beginning: If the Ministry of Interior had any evidence against me, I wouldn’t be working with them today,” he said. “I will submit myself to whatever the judiciary decides,” he added, under “proper legal procedures.”

Hassan Soufan, a former rebel leader and member of the peace committee, acknowledged the “public’s pain and justified anger” over Mr. Saqr’s former militia role, but praised his work with the committee.

“In the context of national reconciliation, we are sometimes compelled to make decisions that prevent escalation and violence, and help ensure relative stability in the next phase,” he said.

The government faces an explosive national dynamic on all sides.

Revenge killings in Syria are now common, human rights activists say, as local residents paste “wanted” lists of former regime members accused of crimes on alley walls, and mysterious vigilante groups vow to hunt down suspects.

In Alawite communities, still fearful and angry after the mass killings on the coast, there are constant rumors that armed insurgencies are being plotted against the new government. That is unnerving local leaders trying to keep the peace.

Nour al-Din al-Baba, the spokesman for the Syrian Interior Ministry, said the sheer size of former regime and paramilitary forces — up to 800,000 people — made it impossible to hold everyone responsible.

Mr. Saqr said his background, not just as an Alawite but as a regime militia commander, gave him the credibility to persuade former regime supporters not to turn away from Syria’s new government.

But the central question remains: “Will the revolution’s public accept them as partners in the homeland?” he said. “The name Fadi Saqr is a test of whether coexistence is possible between both sides of the conflict.”

Muhammad Haj Kadour and Hwaida Saad contributed reporting.

a-syrian-committee-for-civil-peace-angers-those-demanding-justice

Leave a Reply