On an unusually hot morning in June 2024, deep in the Chaco region of northern Paraguay, a small expedition set out on a mission few dare to undertake. The Chaco is a vast, rugged, and largely untamed forest stretching across Paraguay and spilling over into Argentina and Bolivia. It is a place of extremes: harsh heat, dense brush, scarce water, and almost no sign of human life for hundreds of kilometers. For those who know the region, it is also a secret haven for one of the most insidious challenges Paraguay faces today-clandestine narcotrafficking airstrips.

After hours of navigating narrow, winding dirt roads flanked by towering trees, the team finally picked up signs of human presence: a pair of shoes abandoned by the roadside, empty bottles, and eventually, a makeshift camp beneath a thin metal sheet. A motorcycle sat with its keys in the ignition, ready to flee at a moment’s notice.

“You can tell they never stopped operating here,” said Gaspar, the local guide, in Guarani, the indigenous language of the region. Gaspar, born and raised in the Chaco, knows this harsh landscape intimately. His hat and old shotgun-once a tool to fend off jaguars and pumas-are constant companions. Today, his mission is far more dangerous: to track down drug traffickers exploiting the forest’s remoteness.

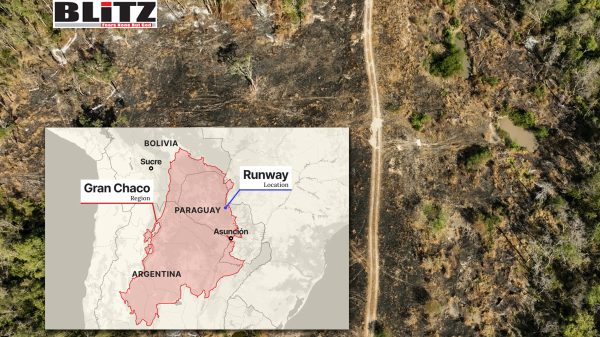

But the journey hit an unexpected roadblock. Several tree trunks and branches had been deliberately laid across the path, a warning or obstacle likely set by those who use the forest as their base. Undeterred, the team launched a drone, which soared over the canopy and revealed a startling sight: a massive brown scar running 1,180 meters long and 55 meters wide, cutting through the lush green of the forest. It was the unmistakable outline of a clandestine airstrip, one large enough to accommodate small and medium-sized planes.

The discovery was as chilling as it was impressive. This runway, the size of 24 Olympic swimming pools, was not abandoned; evidence of recent activity was clear. Burn marks cleared alongside the strip, fresh tire tracks, and connecting dirt roads all pointed to ongoing operations. Even Gaspar, who has seen much of the Chaco’s underbelly, was impressed.

“We are facing a unique situation,” he admitted.

The Gran Chaco spans over a million square kilometers and is one of South America’s last great wildernesses. It is home to unique wildlife like jaguars, pumas, and the vulnerable giant armadillo, as well as indigenous communities including the AyoreoTotobiegosode, Nivaclé, and Yshir. Yet despite its natural richness, the region is known for its punishing climate. Scorching heat, limited water, and difficult terrain make it inhospitable to many, but ironically, these conditions also make it ideal for illicit operations.

Criminal groups trafficking cocaine exploit the Chaco’s isolation and low population density to move enormous quantities of drugs away from the prying eyes of state security forces. The region’s remoteness provides natural cover, while the extensive borderlands between Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina offer multiple routes for smuggling.

Paraguay, until February 2024, was uniquely vulnerable. It was the only country in the region without radar capable of detecting the low-altitude aircraft favored by traffickers. The result? The Chaco effectively functioned as “one large airstrip, large camp, or large warehouse,” according to ZullyRolón, a former minister of Paraguay’s National Anti-Drug Secretariat (Senad).

Senad reports that between 2017 and 2022, authorities discovered and destroyed ten clandestine airstrips in the Paraguayan Chaco alone. Yet these destructions only temporarily slowed trafficking; pilots and gangs quickly repair or rebuild runways, often within days. Investigators estimate that in just one region of the Chaco, these strips saw more than 900 flights in just over a year.

Many of these flights originate from Bolivia, the world’s third-largest coca producer, where sprawling coca plantations exceed 30,000 hectares. Small planes, frequently Cessnas-favored for their versatility and ability to take off from rough terrain-fly drugs into Paraguay’s Chaco. At the airstrips, pilots refuel and offload cocaine before rapidly departing again.

From these secret hubs, cocaine is distributed along two primary routes. The first heads east toward Canindeyú, a border region with Brazil that serves as both a massive consumer market and a transit point for shipments destined for Europe. The second moves south toward ports along the Paraguay River near Asunción, from where drugs are transported via river to Atlantic ports for shipment overseas. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has highlighted this river route as an increasingly important export path for cocaine bound for European markets.

Paraguayan and Brazilian investigations link these airstrips to powerful and dangerous criminal organizations. For example, Brazilian Federal Police accuse Antonio Joaquin Mota-known as “Tonho”-an alleged mafia boss and fugitive, of using an airstrip near the Bolivian border for drug flights. In Paraguay, prosecutors are investigating Uruguayan fugitive Sebastián Marset, on the US most-wanted list, for operating a clandestine runway inside Cerro Cabrera, a protected forest zone in the Chaco. Marset’s network reportedly moved thousands of kilos of cocaine to Europe.

Cerro Cabrera alone saw nearly 900 flights from 2020 to 2021, authorities say. While Marset remains free, several Paraguayans linked to his gang have been convicted. Shockingly, a ruling party senator who allegedly lent his private plane to Marset faces trial for criminal association and money laundering.

The airstrip discovered by the team on this expedition had previously been raided in May 2021 by Paraguay’s Joint Task Force (FTC), an elite security unit. During that raid, authorities found 490 kilos of cocaine, lighting equipment for nighttime landings, firearms, fuel, and generators in a makeshift shed beside the runway.

Despite the raid, the strip was operational again just a few years later. “All the destruction we do is inconsequential,” ZullyRolón said. “When you destroy a runway with explosives, it only puts it out of use for a few days.”

An anonymous pilot with experience flying small planes described the runway as “five-star,” praising its level terrain and size, which can accommodate the favored Cessnas. “Cessnas are air tractors. They can descend and take off anywhere,” he explained.

The airstrip sits on land steeped in a complex history. It was once part of a vast estate purchased in the late 19th century by Carlos Casado, an Argentine businessman who established South America’s first tannin extraction factory there, harvesting quebracho trees. For decades, the local population labored under the company’s rigid control in conditions reminiscent of feudal times. The factory closed in the mid-1990s, and since then the land has been parceled and sold off.

Nearly a tenth of this territory was sold in 2000 to the Unification Church, known as the Moon sect, originating in South Korea. The sale sparked protests from indigenous and local communities fighting to reclaim ancestral lands.

More recently, a company running reforestation projects on part of the land alerted Paraguayan prosecutors to multiple clandestine airstrips and drug trafficking operations on its property. Despite reports, the firm says authorities have responded to only one site. Prosecutors declined to comment.

Despite the region’s inhospitable environment, human life persists in the Chaco. Indigenous groups live in and around the forest, some even maintaining isolated traditional lifestyles. Mennonite communities and cattle ranchers, many descendants of European settlers fleeing persecution a century ago, also inhabit the area.

However, the presence of drug traffickers has brought fear and violence. The guide Gaspar recounted an incident months before the expedition: a group of well-armed men in military uniforms arrived at a local ranch claiming to search for drug gangs. They beat the foreman and terrorized his family. Since then, locals have been barred from the property, and even familiar faces have fallen silent in fear.

“There are no official records of that incident, not even a complaint. No one informed the authorities,” Gaspar said. “People here aren’t used to reporting anything, especially since we’ve learned it’s better not to talk about these things.”

The story of the secret airstrip in Paraguay’s Chaco is not an isolated one but emblematic of a broader and persistent problem: organized crime exploiting geography, local vulnerabilities, and insufficient state resources to sustain a lucrative narcotrafficking network.

Efforts by authorities, while valiant, often fail to keep pace with traffickers’ ability to adapt, rebuild, and intimidate. The Chaco remains a wild frontier where the stakes are high, and the battle against narcotrafficking is as relentless as the heat that beats down on its forests.

Please follow Blitz on Google News Channel

Damsana Ranadhiran, Special Contributor to Blitz is a security analyst specializing on South Asian affairs.

paraguays-hidden-runways-inside-the-chacos-cocaine-superhighway

Leave a Reply